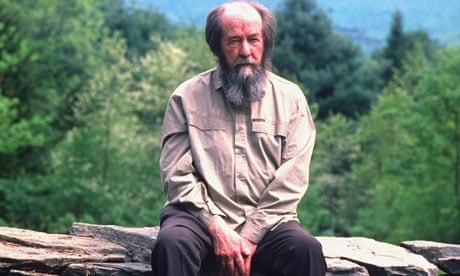

Soviet Dissident, and former Gulag prisoner, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote these remarkable words:

“If only it were all so simple. If only there were evil people somewhere, insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them, but the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being, and who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart? During the life of any heart this line keeps changing place. Sometimes it is squeezed one way by exuberant evil, and sometimes it shifts to allow enough space for good to flourish. One and the same human being is at various ages, under various circumstances a totally different human being. At times he is close to being a devil, at times a sainthood. But his name doesn’t change, and to that name we ascribe the whole lot, good and evil. Socrates taught us: know thyself. Confronted by the pit into which we are about to toss those who have done us harm, we halt, stricken dumb. It is, after all, only because of the way that things work out that they were the executioners and we weren’t. From good to evil is one quaver, says the proverb, and correspondingly from evil to good.”

This is from The Gulag Archipelago, the astonishing literary masterpiece through which the free world learned the full horror of what was happening to millions of citizens of the USSR. It comes at the end of a chapter in which he lists the many and varied methods of torture used, before reflecting on the process by which torturers were tempted, from their youth, with access to unimaginable, appalling power.

What really hits home is where he writes that ‘the line dividing good and evil runs through the heart of every human being, and who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?’

Who indeed? Solzhenitsyn turned to Christ in the gulag, and what he says here is a Christian idea. The New Testament authors wrote that we should be ‘crucified with Christ’, a spiritual transformation in which we 'put to death the old nature’. This is so that we can be 'born again to life in Christ’, a condition in which sin does not ensnare us as it once did. But they were very clear that, even with divine assistance, the old nature does not disappear this side of the grave. This message is given over and over, but is best summed up by the Apostle Paul when he wrote of his own daily struggle: 'I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do.'

So much depends on whether Solzhenitsyn and the apostles were right to say that evil will always lurk somewhere within the human heart. If they are right, then each of us needs to remove the beam in our own eye on a daily basis, and this should take priority over pointing out the specks in other people's eyes.

And yet it is a particular weakness of liberal Christianity that we spend so much time trying to change everything except ourselves. Theology and politics present particular temptations to avoid self-examination. We have so little power to change the world, yet second by second, we make choices about our behaviour that have a great impact on others. So many of us act as though it was the other way round.

What has happened to the Christian preoccupation with our own moral weakness? We can, and should, add our own drop to the ocean that is needed for really big change to occur in the world. But it is only a drop, whereas the decisions we make in our personal lives determine the happiness or otherwise of countless other lives.

Reading Solzhenitsyn’s words about the line between good and evil bisecting my own heart brought me up sharp. In my own life I can choose, far more than I want to admit, the degree of happiness in the lives of everyone I come into relationship with. That’s real power. And yet I, and many other people of faith, spend the majority of our time dealing with evil in the abstract. Is it possible that all the energy we direct towards systemic or ontological evil, and all those posts pointing out the faults in others, represent a far easier path than confronting our own character and motivation?

Does this mean abandoning the causes we support? Not at all, but maybe we should consider the proportion of time and energy we give to theological or political questions relative to the time we spend, or rather don’t spend, wrestling with our own behaviour. Politics and theology matter, but sometimes they are a form of spiritual displacement activity. After all, it’s hard to look too deeply into our own hearts. Hard but necessary, for it is in the personal, not the political, sphere where we hold more power than we can easily own up to.

Even 'liberal Christian' covers a wide church; if pressed I admit to being an 'independant Christian'; contradiction in terms of course. Back to the article. Anyone who attends a regular 'chrisistian church' is going to be asked to look into their heart on a regular basis and to pray for forgiveness/correction also. I still use the BCP a lot since it guides one in that manner. My addition to the article would be that we do of course affect the world around us and its inhabitents and perhaps we should less consider trying to look deeply into ourselves and concentrate more on being present to the present and being alert to our actions and awareness more constantly such that all our interactions with other people are as creative as we can make them. By making what we trust are right actions all the time our concern for our own inner depths may be seen to be of less importance; mainly because the thinking mind can chuck up an endless supply of mental garbage including theories etc. If we can constantly stay aware and stop any of our selfish/evil actions in the bud we then find that we have less failures to report at the end of any day. Hope that helps; thanks for the blog.

ReplyDeletePeter

Thanks for your comment, Peter. Maybe what you're describing is the next step for those of us who feel we need to give more time to dealing critically, though compassionately with ourselves. Having addressed that we then need to find a way of then going out into the world again and working towards some sort of integrated approach.

Delete