As Jesus was being crucified in front of a baying mob he said: ‘Father forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing,' This encapsulated his preaching for the previous three years, best summed up in the Sermon on the Mount: ‘Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you... . For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? … Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.'

To forgive people without repentance and justice is about as counter-cultural as it gets. The wisdom of the world and the instinct of most people, is to forgive only where there is repentance and restoration. And yet Jesus taught a radically different way.

I often wish Jesus had not taught this, and yet there it is. Love your enemies, pray for those who persecute you, and forgive others, even when they are doing you harm. Peter asked Jesus whether he should forgive someone as many as seven times. Jesus replied ‘not seven times, but I tell you seventy-seven times.’ Seems pretty clear to me.

It’s even there in the Lord’s Prayer, 'Forgive us our Sins as we forgive those who sin against us.' Jesus went on to say: 'For if you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you; but if you do not forgive others, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.'

So there’s a lot riding on this and we can’t afford to be confused. Forgiveness is core to Christianity. God will overlook our sins, so we should overlook the sins of others. If not, we deserve to be judged in the same way that we judge others. That’s a fearful judgement.

This really does need spelling out. It’s not okay to withhold forgiveness until you receive justice and repentance, because we will find ourselves judged according to the severity or mercy with which we judge others. We need to forgive.

The idea that we should turn the other cheek always gets a reaction. In Biblical times it was a scandal and foolishness, and it still shocks, confuses and sometimes appalls. People with very little interest in Christianity know that Christians are supposed to turn the other cheek.

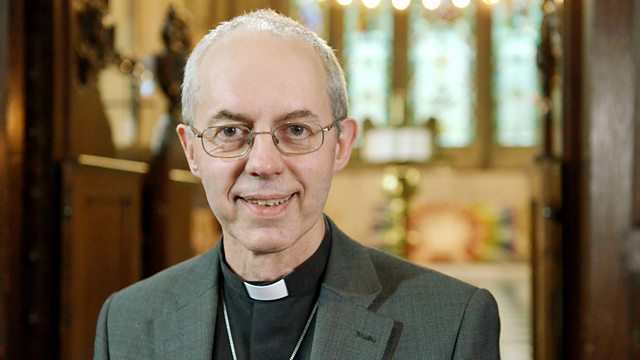

Which is why I was so astonished by Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s appearance on Radio 4’s Today programme last Friday. He delivered a Thought for the Day all about the need for justice, repentance and forgiveness. Then, Justin Webb interviewed the Archbishop and rather brilliantly challenged what he had said, or possibly not said, about forgiveness. I’m including a partial transcript of the conversation because it was so extraordinary.

Justin Webb: You talk in your ‘Thought’ about repentance and forgiveness, and I’m talking more widely now about what should happen to us…do we focus too much, and I’m thinking here about cancel culture, and the narcissism sometimes of the modern era, do we focus a little too much now on repentance and not enough on forgiveness?

Justin Welby: Yes, I think we do, I said in the ‘Thought’ that repentance and justice must go together. Absence of justice requires an extraordinary person to overcome that and forgive in spite of an absence of justice, but we’ve seen in some of the other crises we’ve been facing and will face, not just Covid but also Black Lives Matter and the economic downturn, that there is great injustice and we need a collective turning away from that, which is what repentance means, but we also need to learn to forgive…..

So far so good. Just what one would expect from the leader of the Church of England and the worldwide Anglican Communion. He goes on to describe a project he has contributed to called ‘Together’ and explains that...

On the 5th of July, at 5pm, the aim of that is….to invite people to go outside to thank those who’ve helped us through this dark time, but also to turn, socially distanced, of course, towards each other, to try and rebuild that sense of, yes, you may have done things I didn’t like but we are together, we belong to one another.

There’s nothing on the project’s website about forgiveness or reconciliation, so he may have missed the point, but nevertheless, it was good to hear the Archbishop so focused on the need for forgiveness, which led Justin Webb to ask: Does that mean, then, for instance with statues, that rather than tearing them down, we forgive the trespasses of those whose images we look at?

Great question, I thought. And that’s the point at which the interview took a bizarre turn. See for yourself.

Justin Welby: Well, we can only do that if we’ve got justice, which means the statue needs to be put in context, some will have to come down….but yes, there can be forgiveness, but I hope and pray, as we come together, but only if there’s justice, if we change the way we behave now, and say this was then and we learned from that and changed how we’re going to be in the future, internationally as well.

Justin Webb: But that doesn’t sound like forgiveness...

The two Justins then got into a discussion about what should happen to all the church’s statues, before Justin Webb brought it back to the issue of forgiveness. The Archbishop then said:

For forgiveness, there has to be this turning round, this conversion ,the Pope called it, the change of heart that says we learned from that not to be like that and to change the way we are in the future. And for this country, and for this country in the world...

So there you have it. Without repentance and justice there can be no forgiveness.

This is how most of us feel, and it’s often how we behave. But why is the most prominent Christian in the UK saying this? As an evangelical, Dr Welby puts great weight on the authority of the Bible, so is there scriptural support for him to say that forgiveness is conditional on justice?

You could look at the parable of the Prodigal Son, who wastes his inheritance on hedonism then returns to beg his father to take him back as a lowly servant. The father forgives him, but in response to his son’s repentance. There are many other parts of scripture where a contrite heart is seen as a prerequisite for God’s mercy to flow, and for justice to be established on earth. So yes, repentance is big in Christianity and the Archbishop of Canterbury was faithful to scripture when he said it is necessary. But necessary for forgiveness? Always? Isn’t unconditional forgiveness sometimes the first step towards justice? And more crucially, isn’t it what Jesus did on the cross?

The Bible does say over and over that we should go to God with a contrite heart. But this is addressed to the believer with regard to their own sins. God has every right to expect contrition from us before we receive his forgiveness, but we do not, we must not, claim this right for ourselves when we think of how others have wronged us.

Over and over Jesus explains our relationship with God with parenting analogies. And God forgives us in the way that parents forgive children, and we are to forgive others as we have been forgiven.

What do we think of mums or dads who can never just let it go and move on? Do your children really have to repent and make amends for every infraction in life? What sort of parent never forgives their children, even when they are unable or unwilling to make right the wrong they have done?

Jesus forgave the Roman executioners and the mocking crowd while he was in the throes of death. He told us to love our enemies. He, and the apostles, told us repeatedly that God is merciful, because he blesses and forgives us even in our sins.

Let’s be clear. If you or I have done wrong, we should repent and make amends. If we have been wronged, we may look for restoration and amends, but whether we like it or not, Jesus says the only thing that’s acceptable to God is for us to forgive others in the same way that God forgives us, without us first having to provide or receive justice. You can argue that this is wrong, impractical, absurd, even offensive. But you cannot call it unchristian. Turning the other cheek and loving your enemies is what Christianity is.

Applying this teaching to Covid-19, Black Lives Matter, and the economic downturn is not easy, and I’d be careful of anyone who says that it is. But as we begin the attempt, let’s not be confused about what Jesus taught – even if the Archbishop of Canterbury tells us otherwise.

To forgive people without repentance and justice is about as counter-cultural as it gets. The wisdom of the world and the instinct of most people, is to forgive only where there is repentance and restoration. And yet Jesus taught a radically different way.

I often wish Jesus had not taught this, and yet there it is. Love your enemies, pray for those who persecute you, and forgive others, even when they are doing you harm. Peter asked Jesus whether he should forgive someone as many as seven times. Jesus replied ‘not seven times, but I tell you seventy-seven times.’ Seems pretty clear to me.

It’s even there in the Lord’s Prayer, 'Forgive us our Sins as we forgive those who sin against us.' Jesus went on to say: 'For if you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you; but if you do not forgive others, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.'

So there’s a lot riding on this and we can’t afford to be confused. Forgiveness is core to Christianity. God will overlook our sins, so we should overlook the sins of others. If not, we deserve to be judged in the same way that we judge others. That’s a fearful judgement.

This really does need spelling out. It’s not okay to withhold forgiveness until you receive justice and repentance, because we will find ourselves judged according to the severity or mercy with which we judge others. We need to forgive.

The idea that we should turn the other cheek always gets a reaction. In Biblical times it was a scandal and foolishness, and it still shocks, confuses and sometimes appalls. People with very little interest in Christianity know that Christians are supposed to turn the other cheek.

Which is why I was so astonished by Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s appearance on Radio 4’s Today programme last Friday. He delivered a Thought for the Day all about the need for justice, repentance and forgiveness. Then, Justin Webb interviewed the Archbishop and rather brilliantly challenged what he had said, or possibly not said, about forgiveness. I’m including a partial transcript of the conversation because it was so extraordinary.

Justin Webb: You talk in your ‘Thought’ about repentance and forgiveness, and I’m talking more widely now about what should happen to us…do we focus too much, and I’m thinking here about cancel culture, and the narcissism sometimes of the modern era, do we focus a little too much now on repentance and not enough on forgiveness?

Justin Welby: Yes, I think we do, I said in the ‘Thought’ that repentance and justice must go together. Absence of justice requires an extraordinary person to overcome that and forgive in spite of an absence of justice, but we’ve seen in some of the other crises we’ve been facing and will face, not just Covid but also Black Lives Matter and the economic downturn, that there is great injustice and we need a collective turning away from that, which is what repentance means, but we also need to learn to forgive…..

So far so good. Just what one would expect from the leader of the Church of England and the worldwide Anglican Communion. He goes on to describe a project he has contributed to called ‘Together’ and explains that...

On the 5th of July, at 5pm, the aim of that is….to invite people to go outside to thank those who’ve helped us through this dark time, but also to turn, socially distanced, of course, towards each other, to try and rebuild that sense of, yes, you may have done things I didn’t like but we are together, we belong to one another.

There’s nothing on the project’s website about forgiveness or reconciliation, so he may have missed the point, but nevertheless, it was good to hear the Archbishop so focused on the need for forgiveness, which led Justin Webb to ask: Does that mean, then, for instance with statues, that rather than tearing them down, we forgive the trespasses of those whose images we look at?

Great question, I thought. And that’s the point at which the interview took a bizarre turn. See for yourself.

Justin Welby: Well, we can only do that if we’ve got justice, which means the statue needs to be put in context, some will have to come down….but yes, there can be forgiveness, but I hope and pray, as we come together, but only if there’s justice, if we change the way we behave now, and say this was then and we learned from that and changed how we’re going to be in the future, internationally as well.

Justin Webb: But that doesn’t sound like forgiveness...

The two Justins then got into a discussion about what should happen to all the church’s statues, before Justin Webb brought it back to the issue of forgiveness. The Archbishop then said:

For forgiveness, there has to be this turning round, this conversion ,the Pope called it, the change of heart that says we learned from that not to be like that and to change the way we are in the future. And for this country, and for this country in the world...

So there you have it. Without repentance and justice there can be no forgiveness.

This is how most of us feel, and it’s often how we behave. But why is the most prominent Christian in the UK saying this? As an evangelical, Dr Welby puts great weight on the authority of the Bible, so is there scriptural support for him to say that forgiveness is conditional on justice?

You could look at the parable of the Prodigal Son, who wastes his inheritance on hedonism then returns to beg his father to take him back as a lowly servant. The father forgives him, but in response to his son’s repentance. There are many other parts of scripture where a contrite heart is seen as a prerequisite for God’s mercy to flow, and for justice to be established on earth. So yes, repentance is big in Christianity and the Archbishop of Canterbury was faithful to scripture when he said it is necessary. But necessary for forgiveness? Always? Isn’t unconditional forgiveness sometimes the first step towards justice? And more crucially, isn’t it what Jesus did on the cross?

The Bible does say over and over that we should go to God with a contrite heart. But this is addressed to the believer with regard to their own sins. God has every right to expect contrition from us before we receive his forgiveness, but we do not, we must not, claim this right for ourselves when we think of how others have wronged us.

Over and over Jesus explains our relationship with God with parenting analogies. And God forgives us in the way that parents forgive children, and we are to forgive others as we have been forgiven.

What do we think of mums or dads who can never just let it go and move on? Do your children really have to repent and make amends for every infraction in life? What sort of parent never forgives their children, even when they are unable or unwilling to make right the wrong they have done?

Jesus forgave the Roman executioners and the mocking crowd while he was in the throes of death. He told us to love our enemies. He, and the apostles, told us repeatedly that God is merciful, because he blesses and forgives us even in our sins.

Let’s be clear. If you or I have done wrong, we should repent and make amends. If we have been wronged, we may look for restoration and amends, but whether we like it or not, Jesus says the only thing that’s acceptable to God is for us to forgive others in the same way that God forgives us, without us first having to provide or receive justice. You can argue that this is wrong, impractical, absurd, even offensive. But you cannot call it unchristian. Turning the other cheek and loving your enemies is what Christianity is.

Applying this teaching to Covid-19, Black Lives Matter, and the economic downturn is not easy, and I’d be careful of anyone who says that it is. But as we begin the attempt, let’s not be confused about what Jesus taught – even if the Archbishop of Canterbury tells us otherwise.

The Today Programme on 26th June 2020, Interview with Justin Welby starts at 2 hours, 33 minutes and 10 seconds. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000k9qx

Comments

Post a Comment