This crisis could be leading us to a 1945 moment, in which an economically ravaged nation reimagines what is possible, and what it will stand for. Maybe we will emerge into a poorer, but fairer world, and business as usual will go out of business. But as we rethink our national story the churches must do the same. And this starts with correcting a huge flaw in the traditional understanding of the crucifixion.

Christianity’s understanding of salvation (soteriology) is grounded in the Hebrew Bible. There we find countless examples of salvation, any of which could be used to contextualise the crucifixion. Take your pick from Noah’s ark, Joseph’s rescue of his brothers, Abraham’s near sacrifice of his beloved son, Isaac, or Moses leading the Israelites out of slavery, to the promised land. There’s the restoration of Job, Noah in the Whale, Daniel in the Lion's Den, David and Goliath. David’s inspired victories as King, Esther rescuing Israel from genocide through cunning, or the Israelites in captivity in Babylon returning to the Holy Land after a geopolitical shift that was foreseen in prophecy. On other occasions, prophets saved the nation by declaring which battles could and couldn’t be won. Sometimes the nation was saved because a prophet persuaded the King to surrender. And then there’s the Day of Atonement, a priestly ritual for the symbolic cleansing from sin.

These are just a few of the salvation motifs in the Hebrew Bible that could have been applied to the crucifixion of Jesus. But the church, for centuries, has fastened on just one.

What happened to Jesus on the cross, has become known as the Atonement, because the church frames the crucifixion in the context of the Day of Atonement, an Ancient Israelite festival, outlined in Leviticus. On this day, the High Priest ceremonially placed the sins of the people on to a sacrificial lamb, and so cleansed the people of any sins they had committed over the past year. The lamb had to be the first born, and without blemish.

The early Christians came to believe that Jesus was the ‘Lamb of God’, a sacrifice made by God, on our behalf, to cleanse us from sin. Like the lamb on the Day of Atonement, Jesus, as Son of God, is the ‘first born’ offspring, and is without blemish. According to Leviticus these sacrifices have to be repeated annually, (on the Day of Atonement), because there will always be some way in which the people have transgressed God’s law. The New Testament authors, however, reasoned that the crucifixion replaced the Day of Atonement, and, because God had initiated a sacrificial cleansing involving his own Son, it was a perfect, and permanent, sacrifice, the effects of which far exceed the Levitical version.

Christianity teaches that, unlike the ancient sacrificial system outlined in Leviticus, the sacrifice of Jesus only needs to happen once, and then anyone who believes in Jesus will have their sins placed upon Jesus, the Lamb of God, in his crucifixion.

Jesus dying on the cross has always been seen as an act of salvation - but why? And what does salvation mean? Saved from what?

Christianity’s understanding of salvation (soteriology) is grounded in the Hebrew Bible. There we find countless examples of salvation, any of which could be used to contextualise the crucifixion. Take your pick from Noah’s ark, Joseph’s rescue of his brothers, Abraham’s near sacrifice of his beloved son, Isaac, or Moses leading the Israelites out of slavery, to the promised land. There’s the restoration of Job, Noah in the Whale, Daniel in the Lion's Den, David and Goliath. David’s inspired victories as King, Esther rescuing Israel from genocide through cunning, or the Israelites in captivity in Babylon returning to the Holy Land after a geopolitical shift that was foreseen in prophecy. On other occasions, prophets saved the nation by declaring which battles could and couldn’t be won. Sometimes the nation was saved because a prophet persuaded the King to surrender. And then there’s the Day of Atonement, a priestly ritual for the symbolic cleansing from sin.

These are just a few of the salvation motifs in the Hebrew Bible that could have been applied to the crucifixion of Jesus. But the church, for centuries, has fastened on just one.

What happened to Jesus on the cross, has become known as the Atonement, because the church frames the crucifixion in the context of the Day of Atonement, an Ancient Israelite festival, outlined in Leviticus. On this day, the High Priest ceremonially placed the sins of the people on to a sacrificial lamb, and so cleansed the people of any sins they had committed over the past year. The lamb had to be the first born, and without blemish.

The early Christians came to believe that Jesus was the ‘Lamb of God’, a sacrifice made by God, on our behalf, to cleanse us from sin. Like the lamb on the Day of Atonement, Jesus, as Son of God, is the ‘first born’ offspring, and is without blemish. According to Leviticus these sacrifices have to be repeated annually, (on the Day of Atonement), because there will always be some way in which the people have transgressed God’s law. The New Testament authors, however, reasoned that the crucifixion replaced the Day of Atonement, and, because God had initiated a sacrificial cleansing involving his own Son, it was a perfect, and permanent, sacrifice, the effects of which far exceed the Levitical version.

Christianity teaches that, unlike the ancient sacrificial system outlined in Leviticus, the sacrifice of Jesus only needs to happen once, and then anyone who believes in Jesus will have their sins placed upon Jesus, the Lamb of God, in his crucifixion.

This model of atonement is known as Penal Substitution. It says that only perfect behaviour makes us fit for the new heaven and the new earth, so without Jesus taking our place before God, we would all be judged unworthy to enter the Kingdom of God.

But here’s the problem: if the crucifixion of Jesus is primarily about the Day of Atonement, then why didn’t he get crucified on the Day of Atonement? All four gospels make it clear that Jesus timed his entry into Jerusalem so that he could die at Passover, not the Day of Atonement. Dying at Passover was the plan, not some random coincidence.

Passover commemorates Israel’s escape from slavery in Egypt. In particular, it refers to the twelfth chapter of Exodus. In this well-known story, Moses demands nine times that Pharaoh let his people go, and nine times Pharaoh refuses. Each time, God responds with increasingly severe plagues. Passover focuses on the events surrounding the tenth and final plague. God instructed Moses that all the Hebrews were to eat a lamb and smear its blood on their door. That night, the Angel of Death passed over Egypt, striking dead all the firstborn - including Pharaoh’s son. The Hebrews were spared - thanks to the blood of the Lamb on their doors, and Pharaoh finally agreed to free them.

See how the blood of a lamb features once more, but in an entirely different context? This is a story about liberation, not sin! Jesus was determined to die at Passover, so isn't it glaringly incongruous to make the crucifixion all about having your sins nailed to the cross? Don’t Jesus’s actions speak to us more clearly, and loudly than all the theological formulations the church has devised to convince us that the cross is just about our personal sins?

To be sure, Jesus set very high ethical standards for his followers. He wanted us to deal with the sin in our lives, but it wasn’t the centrepiece of his mission. He could easily have engineered circumstances so he would die on the Day of Atonement, but he didn’t. He died at Passover, when the people were celebrating freedom from slavery. This truth has been hidden in plain sight for two thousand years. How could the church fail to notice this?

Maybe the church would have seen more clearly if the it had kept its distance from the state. But within a few hundred years of the crucifixion, Christianity had become the official religion of the empire that had killed Jesus, and in which slavery was commonplace. Centuries later, Britain, along with other Christian nations, built its own empire and participated in the slave trade. In all these national ventures the church was intertwined with state power. How could these churches admit to themselves that the cross was more to do with national and communal liberation than it was to do with personal sin?

To be fair, there have always been a minority of theologians that followed a liberation model of atonement, known as Chrestus Victor. This sees the cross as a victorious liberation, but it over spiritualises the story. It says that Jesus defeated Satan on the cross, not slavery or empire. Chrestus Victor theologians say that Jesus liberated us from the power of Satan in our lives, and that brings it back to personal sin again. But dark spiritual power takes shape in human oppression, and sin can be systematic and structural.

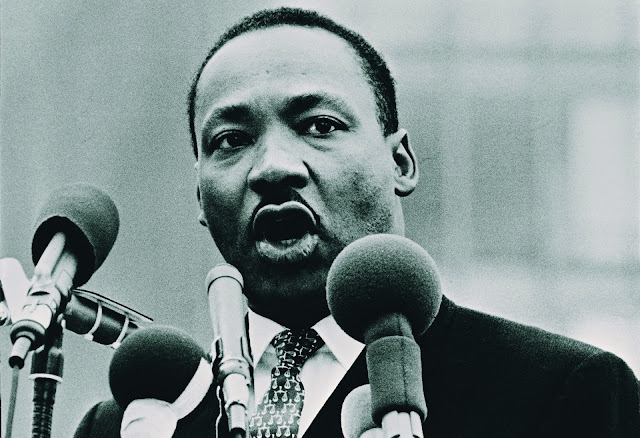

The truth can’t be buried forever, though. Martin Luther King got it, that's why he referred so often to the story of Israel’s escape from Egypt. Across the world, oppressed people couldn’t help but notice that Jesus went to the cross during a commemoration of national liberation. The rest of us need to cotton on to this, too. How could the church get this so wrong? How different could things have been.

PS

It’s vitally important to remember that Passover and the Day of Atonement are still important annual festivals in Judaism. The proper Hebrew names for these festivals are Pesach and Yom Kippur. Christianity finds context in these festivals as they were practiced two thousand years ago, before the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. They are quite different now. Please, find out more by visiting these links.

Comments

Post a Comment